The Last Girl to Die starts with a desperate family. Their sixteen year old daughter has vanished after they move to the island of Mull, far off the coast of Scotland. But with hostile local and the Police that don't seem to care, the parents turn to private investigator, Sadie Levesque.

Sadie is the best at what she does, so when she discovers Adriana's body in a cliffside cave, her body posed with a seaweed crown carefully arranged on her head, Sadie knows she is dealing with something truly sinister. But as Sadie begins to look for the truth and digs into the island's secrets, danger is edging closer to her...

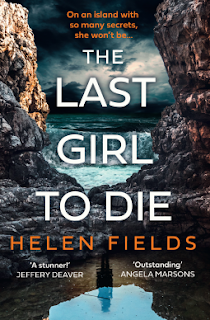

I am thrilled to share an extract with you from Helen Fields's The Last Girl to Die as this sounds like a deliciously creepy thriller and you know me with creepy thrillers.

Now, before I tease you with an extract (I think it's the start of chapter 11, but I might be wrong), I just want to thank Olivia from Midas for emailing me about this book, tempting me with the blurb and going "Oh, do you want to share an extract?". And, if you want to know more about the book or the author's other works, you can pop over to helenfields.com or say hi to Helen on Twitter at @Helen_Fields.

Lance Proudfoot promised to email me the address of Jasper Kydd’s farm. Rather than sit in my room and wait, I opted to exercise and get breakfast from the bakery on the bayfront. This time I took a path due west of the town, punishing my legs by striding up and down the hills and enjoying the view. As the mist blew away, the sky revealed itself to be clear with only a few rippling clouds adding texture. Mull was every conceivable shade of green and blue. It was a new day and I had a job to do. Buying a croissant and takeout coffee from the bakery, I returned to the hotel and got ready for the drive to Kintra. It was only when I saw the tyres of my hire car that I realised my plans for the day were going to be pushed back.

All four of them slashed. I’d been freaked out by the seaweed crown and scared by the rabbit thrower, but now I was absolutely furious. Someone didn’t want me there, which made me all the more determined to stay. Of course there was no CCTV covering the carpark. The hotel receptionist looked at me as if I’d just flown in from New York wearing enormous sunglasses, a fur coat and complaining that the ice wasn’t cold enough. I called the local garage who promised to fetch the car by midday. It was 6.30 p.m. when they phoned to say the tyres had been fitted, and 7 p.m. before I’d paid my bill and had the keys in hand.

*

The 56-mile trip to Kintra took me an hour and a half in the dark. Twice, animals dashed across the road and I had to brake to a standstill. I didn’t want another rabbit on my conscience. There was one road in and out. I missed the farmhouse as I passed it, reaching an impasse at an arc of houses that looked out to sea. A forlorn fishing boat sat on what I guessed was a front yard – a mossy green patch with boulders rising from it. In Kintra, you fished or you farmed. It could have been the ends of the earth.

Windridge Farm was a two-storey with white plaster that had been attacked by too many decades of sea spray to last much longer. It sat a quarter of a mile back from the road, windows dark, as if the very building had shut its eyes to the civilisation beyond. I’d have phoned if that had been a possibility, or put a note through the door if I’d had a spare day. As it was, I left my car in the driveway and knocked on the oak door. It occurred to me that Mr Kydd might already be in bed. He had to be close to eighty years old, and what was there to do in the evening if you lived alone? The man I’d seen at The Blether certainly wasn’t spending his evenings watching box sets. He’d been inconsolable. The news of Adriana’s death must have dredged all his grief from where he’d shoved it and brought it up as fresh and sharp as the day his daughter failed to come home. Perhaps he wasn’t sleeping. Perhaps he’d decided he couldn’t relive those horrors again. Or maybe nature had finally been kind.

I looked from the house to my car. The most sensible course of action was to go back to my hotel and ask Sergeant Eggo to check up on Mr Kydd in the morning. That might be too late – I couldn’t stop the voice in my brain that always spoke up at moments like those and never brought good news. What if he’d had a stroke? He could have been lying there, unable to move.

‘Oh, for crying out loud,’ I answered myself. ‘I’ll need a flashlight.’

Torch in hand, I headed first for the shed and picked up a shovel. It never ceased to amaze me how many people left the tools necessary to break into their house in a small unsecured wooden structure just a few feet away from their back door. Windridge Farm dated back at least a hundred, more likely two hundred years. Slotting the shovel into the frame and pressing down was all that was necessary to open the kitchen window a crack then slip my fingers in and slide it up.

‘Mr Kydd?’ I shouted. ‘My name’s Sadie Levesque. I just want to check you’re okay.’ Paused, listened. ‘Hello?’ Nothing. ‘Mr Kydd, I’m coming in. Please don’t be alarmed.’ The kitchen window was too high to get a leg in. I went head first and dragged myself across the windowsill and over the draining board.

The house was cold and silent. Only the rush of the breeze could be heard, a constant shushing in the darkness. I ran the torchlight around the walls until I located the light switch. The single orange bulb did little to illuminate the place, casting a pool of light downwards onto the red tiled floor. I called out again but my voice was met by nothing except a dull stillness, as if the house itself were dead.

No comments:

Post a Comment