BLOG TOUR TIME!!! And we are dealing with spies!

Devil Darling Spy is the sequel to the shortlisted Costa Children's Book of the Year 2018, Orphan Monster Spy, and we return to Sarah who, after her last mission, is back in Nazi Berlin, spying her way through champagne-filled parties. But not for long as she is thrown into a dangerous journey into central Africa to stop the mysterious White Devil who is planning to unleash a deadly virus, using it as a weapon...

So... try not to watch or read the current news when reading this, ok?

I am thrilled to have Matt Killeen on the Pewter Wolf, chatting about the top 5 badass women in fiction. Because why the heck not!

Now, before I hand it over to Matt, I just want to thank him for writing this guest post in such a short time (I kept "oooh" and "erm"ing over what we wanted this post to be!) and to both Katarina and Jessica at Usborne for allowing me on this tour and helping me out!

Now, before I hand it over to Matt, I just want to thank him for writing this guest post in such a short time (I kept "oooh" and "erm"ing over what we wanted this post to be!) and to both Katarina and Jessica at Usborne for allowing me on this tour and helping me out!Also, if you want to say hi to Matt, pop over to his Twitter at @by_Matt_Killeen and if you want to know more about Devil Darling Spy, you can pop over to Usborne for more info. Now, Matt's top 5 fictional badasses!

Asked to choose my top five “bad-ass” fictional women, I suffered a sudden deja-vu. Back in 2018 when Orphan Monster Spy was released, I was asked to write about some my favourite fictional heroines for “a few” blogs…I got over-excited, added real women and wrote far too much. Eventually Usborne chose to release the sum total of this work as The Women Who Made Me a Feminist. I’m not going to recycle these – so no General Leia Organa, no Newt and no Katniss this time – but I am cheating by using one, Peppermint Patty, that missed that book’s publication date.

“Bad-ass” is a catch-all term that works better than strong or kick-ass, in my opinion. The latter two terms are often implicitly male, as if male attributes are the only valuable ones. I once heard someone say, “we would happily trade all the strong female characters for well-written ones.”

Can a fictional character be as inspiring as a real woman, in Feminist terms? Probably not. I know there are those who see “inspiring women” lists that feature book and film characters as less than helpful…but can fictional women be truly empowering? To deny that would be to deny the importance of representation and the very real part that that fiction plays in the development of our personalities. Would I be the person I am without General Leia? Only possibly...

Patricia "Peppermint Patty" Reichardt from Peanuts

My school had one or two. They were better footballers than we were, yet they weren’t allowed on the boy’s playground to play. These girls wanted to play for the school but couldn’t. Even to eight year olds, we knew this was unfair. Why shouldn’t Shaz play with us if she wanted to? While the boy’s playground would probably have been less supportive of someone who wished to move in the other direction, Shaz and her kith established a principle, that even in the difference intolerant 1970s, gender norms weren’t fixed in the way that we had been taught.

The popular term for this, “tomboy”, was an awkward pejorative description, reducing some complex notions of identity down to “wanting to be a boy”. It is fitting then that one of the most famous tomboys of the era was actually a highly nuanced character in an emotionally multifaceted fictional world.

Patricia Reichardt does not want to be a boy. That much is clear from her refrain, “don’t call me sir.” Peppermint Patty just loves baseball and sandals, while she doesn’t like dresses. There are a number of better words today to describe fluid gender identity, such as genderqueer, and Patty is not at all confused as to who she is. She is clear that it is the planet that has the problem.

The Dress Code series, where Patty is compelled to wear a dress and shoes to school, is a deeply traumatic demonstration of what happens when society imposes its rigid gender notions on those who are uncomfortable with them. She suffers profound misery and sleepless nights, as well as a sense of powerlessness and hopelessness. As a pacifist I don’t believe in resorting to violence, but Patty’s pounding of her first tormentor – “all right, who’s next?” she shouts – is very satisfying and a predictable result of removing someone’s agency. Eventually she defies the Dress Code and hires Snoopy as her attorney (although he prefers the term barrister) to help her argue that the Dress Code infringes her civil liberties, or as she says, “it’s piggy.” She is found guilty and her punishment, to read the US Constitution every lunchtime only further convinces her of her righteousness. “If they ever lower the voting age to seven, LOOK OUT!”

She is not without her moments of insecurity. She struggles with some emerging heterosexual tendencies and the fact that the world appears to expect a very different looking girl to act on them. But this sophisticated character development aside, she is largely at home in her own skin. She is who she is and makes no apologies for it.

Patty is also a good person. She is a talented ballplayer, but unlike many of the gifted sportspeople I knew in the real world, she is not a bully. Impatient, yes, but never nasty. She draws no real pleasure from lording over her hapless friend Chuck. She is a child of a single parent in an economically deprived part of town and who struggles with her education to the point of being held back at least one grade. She is perpetually exhausted at school as her father works late and she cannot sleep until he returns home. These are all factors that might have contributed to a less than compassionate personality. Yet she remained, as creator Charles Schulz described her, “forthright, doggedly loyal, with a devastating singleness of purpose.”

Peanuts was a very special cartoon in my childhood. Unlike the alternative diet of ruthless soldiers, unfeasibly gifted sporting heroes and overpowered superheroes, the tales of Charlie Brown and friends had an air of endless melancholia that effortlessly encapsulated my own nascent depressive symptoms. The failure, struggle and loss that permeates their misadventures mirrored my own feelings and experiences.

Schulz himself would not have recognised a term like non-binary, but by creating Peppermint Patty with consideration and emotional honesty, he created a character every bit as important as his small part in the civil rights movement. In 1972, he had a genderfluid daughter of a single-dad sat behind a child of colour whose father was serving in Vietnam …I think his instincts were right on the money.

Anne (with an E) Shirley from Anne of Green Gables

Anne of Green Gables is a book I came to later in life as I explored all things feminine in my teens. I already knew that a) GURLS things were, in fact, ace, having read Malory Towers as a bit of ironic anti-masculine posturing, like my Miss Selfridge bag pencil case, only discover I loved the whole thing, and b) having watched the excellent Megan Follows mini-series, I fell head-over-heels for the tragical misadventures of Canada’s most famous orphan and her puffed sleeves. I sought out L. M. Montgomery’s works and, man, they did not disappoint. Oh, l loved her writing and I couldn’t get enough of it.

Unlike Pollyanna, who was a proto-Mary-Sue incapable of acknowledging real misery, Anne understood tragedy perfectly well, and recognised abuse when she suffered it. Her despair has “depths”. She just found enough inner strength to imagine better and not let that hope destroy her. This makes Green Gables a real challenge to her, providing the real possibility of a beautiful redemption, only to have it removed. Is there a more heart-breaking moment in literature than when Anne, the “animation fading out of her face,” realises that Marilla has been sent a girl by mistake?

“You don’t want me?...I might have expected it. Nobody ever did want me.”

But Anne is the kind of girl who would make up her mind to enjoy the ride back to the orphan asylum, while admitting that her life was “a perfect graveyard of buried hopes.” She’s the kind of girl who draws comfort from those words, because they sound “nice and romantic.” It is this emotional depth that saves her. In the hands of someone who has only forgotten how to be compassionate, her countenance is something that would haunt them “until their dying day” were they to ignore it.

Of course, she is unlike Pollyanna in one other major respect. Anne has a TEMPER. There is a real fire inside that girl. It’s not surprising considering her life until her arrival in Avonlea, but the fact that she isn’t burning down the world every moment of every day is a real triumph of human spirit. I was once told by a therapist, probably inappropriately, that bearing in mind my childhood experiences, I could, possibly should, have become a bully, an abuser, a monster…yet I did not and every day that I was not these things was a victory. She suggested that this was something to be proud of and draw strength from. This idea always made me think of Anne.

See, I am bound to that character. Someone who had their imagination and their romantic ambitions and their wits and sometimes it seemed like that was all they had, in a world that mistreated and exploited them, dismissed them or thought them a joke or worthy of having their pigtails pulled. I have dyed my hair green countless times, metaphorically speaking. I have yelled at the Rachel Lyndes of life, when I should have held my tongue. And, naturally, if I fall or have an accident, I am not dead, but fear I am rendered unconscious.

I was a teensy bit disheartened that Anne didn’t, in fact, follow Gilbert to war and become a combat medic, as she does in one of the TV sequels. I think that was entirely in fitting with her character, but I think that was a step too far for Ms Montgomery to contemplate, a women ahead of her time, but a time so long ago. Meanwhile, I live everyday trying to be a bit more Anne:

“Not failure but low aim is crime. We must have ideals and try to live them, even if we never quite succeed. Life would be a sorry business without them. With them it’s grand and great.”

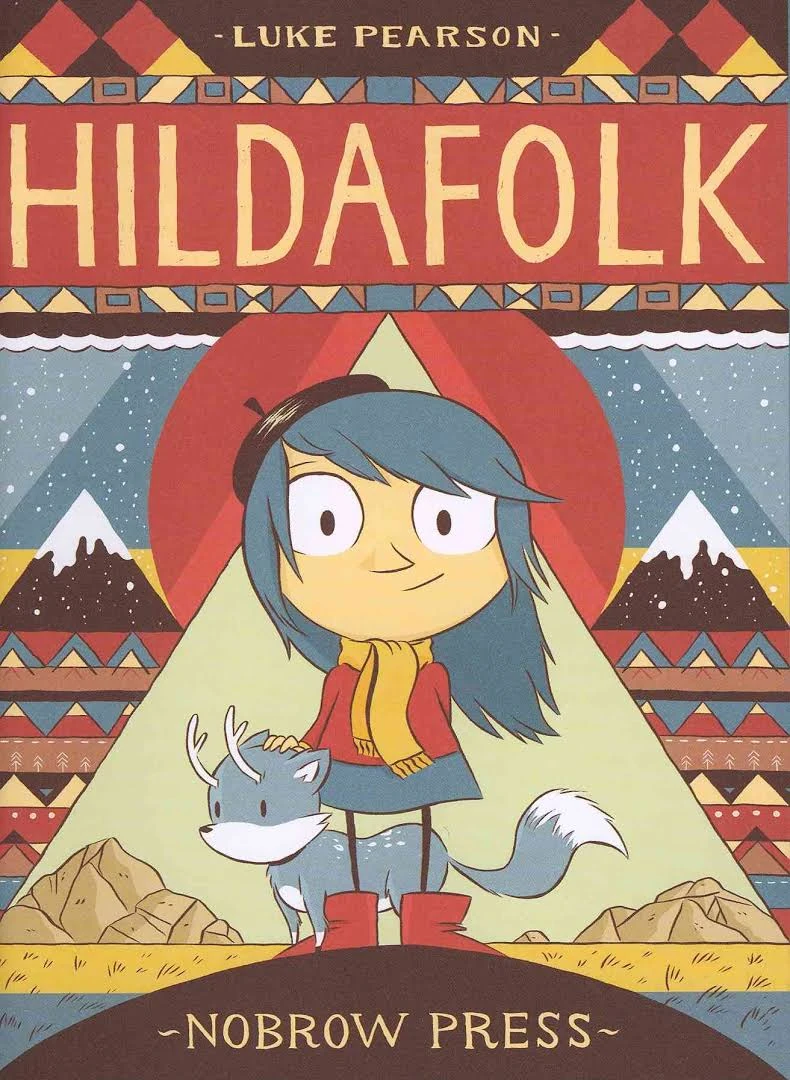

Hilda from Hildafolk

Raising children requires a certain loss of the self. You are obligated to share your germinal-human’s desires, interests and viewing habits, and this can be excruciating. I will never get the time spent watching Fireman Sam or Paw Patrol back, nor the time I spent creating elaborate analyses and subtexts (Paw Patrol as the endgame of public sector privatisation, for example, or Skye’s constructive dismissal case) just to stop myself from becoming spiritually lobotomised, a zombie of brainstem-powered acquiescence, giggling quietly at the pretty colours.

Sometimes, because you are a good person and providence smiles upon you, the TV gods bewitch your child with a love of something truly, uniquely brilliant. Luke Pearson’s children’s graphic novels, Hildafolk, and their resulting TV series, Hilda, are such a thing, and at their heart is the titular character, a young blue-haired girl of stunning hutzpah, curiosity and self-reliance.

Hilda and her deer-fox Twig run through the countryside of her magical-realist Scandinavia. There she meets a cast of creatures pulled from northern European folklore, before moving to the town of Trolberg as part of her mother’s ongoing efforts to give her something approaching a normal life. However, normality in Hilda’s world involves paperwork loving elves, trolls, giants, huge black hounds and the ubiquitous ever-migrating woffs. Even joining the Sparrow Scouts and making some human friends leads to daring exploits, because such is the life of an adventurer.

She cares, yet she is no pushover. “What’s the matter with you?” Hilda howls at some children throwing stones at birds. She’s new in town, they represent acceptance, but they have crossed the line and, alone or not, she is having none of their crap. She is the kind of person who turns Knock Down Ginger into a conversation about someone’s garden.

The whole thing works, like all great entertainment for children, on multiple levels. It’s an adventure. It’s a lesson on ecology. It’s a tale of new friends and small families. It’s a warning on the folly of human pride amongst the vastness of cosmic scale. And Hilda’s beret and red Uggs carry it all.

As a parent I do find myself empathising with Hilda’s mother’s concern that her daughter have a few more, you know, homo sapien friends, while appreciating the exquisite tension between what our children are and what we hope for them.

Onscreen, Hilda herself is voiced by Bella Ramsey, Game of Thrones’ Lyanna Mormont or The Worst Witch’s Mildred Hubble, depending on your age, and she brings both the vehement and determined wisdom, and careless juvenile joie de vivre of those contrasting personalities to the role. That’s some dichotomy and it’s an excellent performance.

I won the SCBWI Crystal Kite for the British Isles and Ireland for Orphan Monster Spy in 2019. It was a long-held ambition, a powerful validation of my work by my peers and a real career highlight. It’s presented at a costume party, so I received it dressed as Hilda. Because, who better?

Glimmer from She-Ra & the Princesses of Power

I hated the original She-Ra: Princess of Power, and it’s steroid-boosted brother He-Man, for the schlocky, wafer-thin extended toy commercials they were. It seemed to an aging pre-tween to be the moment that animation lost its soul. This wasn’t entirely accurate. Most children’s animation that preceded it, like Scooby-Doo, was cheap, cynical and recycled. But for someone growing up on Bagpuss and Camberwick Green, the drop in quality was evident. It also lacked the batshit-wild, scattergun quirk of anime adaptations like Battle of the Planets.

So I ignored the appearance of the continuity reboot on Netflix, until a good friend pointed out that the showrunner was Lumberjanes co-creator Noelle Stevenson. I was still sceptical, but watched it anyway. I soon realised that there had been a Princess-of-Power-shaped whole in my life, and only now could I experience true happiness.

Managing to be both hilarious, poignant and exciting, it’s such an ensemble piece that I could have chosen any of the characters, as they are as funny, inspiring, quirky and nuanced as each other. Villain Catra is one of entertainment’s most complex, sympathetic baddies and her love-hate relationship with Adora / She-Ra is one of the most emotionally charged old friends, new enemies paradigms in fiction, if not the ultimate ship.

But it is Glimmer, the teleporting Princess of Bright Stone, that has been holding the Rebellion against the invading Horde together single-handed, at least its spirit, long after everyone else has slunk off to their castles to lick their wounds. And she walks that talk, blinking in and out of battles and throwing aggressive fist-to-face energy balls whenever needed, and whenever she isn’t grounded. If her magic didn’t expend and require recharging – and her mother allowed it – she could win the entire war on her own. Not bad for a Princess whose power is, as she describes it, sparkles.

She’s a warrior by necessity, although this war has been going on her whole life, and she has maintained her sense of self. Not for her is the ugly martial utilitarian pragmatism of the Fright Zone. No, floating beds of scatter cushions are the order of the day. She has not allowed the war to change her. In terms used in Devil Darling Spy, Glimmer has grown strong, she has not grown hard. This means that when a saviour does appear in the form – of all things – a Horde Force Captain, it doesn’t take Glimmer long to overcome her own anger and jealousy to welcome that messiah into her home, her life and her heart. Adora is a very damaged woman, and simply would not be able to go on without Glimmer’s love and support.

The entire cast are more realistically proportioned than their predecessors despite the stylistic visuals, which admittedly wasn’t hard, but this is nowhere clearer than in Glimmer’s design. To even discuss it, reveals much about how we are indoctrinated, how we are primed to judge and control female presentation.

Glimmer has, for want of a more direct terminology, a big ass. Not in the male gaze-y J-Lo sense, but in the way women can be sense. Her thighs are…huge? That’s “huge” in the way people can be, and we are just not programmed to expect from TV. Not in fact huge. Statistically typical. Glimmer is just that shape. She shows very little sign that she’s even aware of it, or what someone might think of it and we can be pretty certain that she’d have very little time for anyone who thought less of her because of it.

This is, of course, viewed through male allocishet eyes. Despite my best efforts at empathy, listening and research, Butchy Femme (or 4-5 on the Futch Scale) is just a label. I have no pony in that race and cannot begin to understand what she may or may not mean to those who do, much as I support them. But what I see is freedom, inclusion and self-actualisation writ large. I feel that power. How potent…no, not potent…how fertile must the energy the girls and young teenagers watching Glimmer be experiencing?

In the bin-fire that passes for the world right now, Glimmer’s awesomeness, in fact her very existence, is vital and essential. She will make humankind better company in years to come.

April from Lumberjanes

Oh my, Bessie Coleman! As you’ve just read, I am also an evangelist for the sequential art masterpiece Lumberjanes…making me a Lumber Jumbie, apparently. Created by Shannon Watters, Grace Ellis, Brooklyn A. Allen and She-Ra showrunner Noelle Stevenson, this comic series tells the story of one cabin of teenage girls at Miss Qiunzella Thiskwin Penniquiqul Thistle Crumpet's Camp for Hardcore Lady Types, a summer camp for Lumberjane Scouts…that just so happens to lie on a time-bending nexus of supernatural activity that requires some concentrated, smart and fearless ass-kicking.

Again, I could choose any of the characters: the wise and thoughtful Jo. The anxious but loving punk, Mal. The quiet archer Molly, whose racoon skin at is actually a live racoon. The tiny and easily-distracted, force of nature and one-time god of all creation, Ripley. The strict but caring Jen, the camp counsellor, whose Sisyphean task is to stop Roanoke Cabin getting into trouble with dinosaurs, three-eyed foxes and teenage Greek Goddesses.

My choice, however, is April, the diminutive titian-haired powerhouse. She is fearless, driven in her pursuit of excellence, scouting badges and winning via the conduit of glitter, glue and necessarily aggressive self-defence. Her curiosity and the joy she draws from it are best summed up in one of her first lines: “And we followed her because. Duh. Bearwoman.”

She’s not perfect. She’s an idealist and a romantic to the point of being a pushy busybody, once causing a riot at a merperson rock festival, because she couldn’t resist the temptation to stick her oar in. If there’s a trope to fulfil, like getting a band back together, she will not let it lie. Let’s call it tenacity.

I won’t congratulate her on her life-long friendship with Jo, a trans girl, because you don’t get points for being a decent human being. But it’s nice to know where April stands nevertheless – trans women are women and if Barney feels more comfortable being a Hardcore Lady Type, April will help facilitate that transition too.

April is also a girly-girl. Don’t tell her she can’t wear pastels, or be into make-up. She will arm-wrestle you into rethinking your preconceptions. In the era of feminists don’t wear pink and anti-princess misinformation April is who she is, proving, if it needs stating, that inclusion is for everybody. It’s in the name.

OK so this is *excellent*! I love how it's almost an extension of The Women Who Made Me A Feminist. Although now I really want to re-watch She-Ra.

ReplyDeleteCora | http://www.teapartyprincess.co.uk/